In control theory, there are only a handful of ways to control people or things. One is bureaucracy, a centralised, hierarchical, and administrative form of control in which system-wide goals and decisions are made top-down, and rules and procedures control people’s behaviour.

The opposite would be a decentralised marketplace with price competition and competition over market share. Goals and decisions are left to individuals who have localised knowledge and specialised expertise, and information is communicated through the price mechanism. For markets to function effectively, the police and courts play a function to prevent property rights violations.

Why are bureaucracies not good?

Definition:

Bureaucracy is a hierarchical organisational system characterised by rigid rules, centralised authority, and specialised roles, designed to enforce uniformity but often criticised for inefficiency and expansionist tendencies. In both government and large institutions, it replaces market-driven incentives with procedural compliance, as seen in tax regulations or corporate HR departments that prioritise legal mandates over productivity

Bureaucracy is an organisational system characterised by red tape, crippling complexity, top-down control and the diffusion of accountability. Typically found in government departments or large corporations.

1. Gammon’s law of bureaucratic displacement

According to Gammon’s law of bureaucratic displacement, bureaucratic systems act like "black holes" in the economic universe, simultaneously sucking in resources while shrinking in terms of emitted production. This means you replace productive work with what Gammon defines as useless administrative procedures.

Suppose you compound this with the empirical Price’s law, which states that the square root of the number of people delivers 50% of the value to the business. In that case, having those hyper-productive individuals waste time on administrative procedures means your productivity and output fall dramatically.

2. Tainter’s Theory of Collapsing Societies

The Second Law of Bureaucratic Complexity, also known as the Iron Law of Bureaucracy, states that "Systems complexify. Any bureaucratic system will tend to accrete complexity and layers of control, unintended by the original designers but necessitated by the broader context.”

According to Tainter’s theory of collapsing societies, when societies reach a point of rapidly declining marginal returns on their investments in solving complex problems, that society will collapse. Tainter cites the Roman Empire, classical Mayan civilisation, and Chacoan society as examples.

“Britain saw one of the most stunning national collapses ever seen in human history. The British went from the wealthiest, most technologically and culturally strongest nation in the world with the largest empire ever in history to a fourth-rate nation. The sun used to never set on the British Empire, but now its people are in poverty, and it has nothing worthwhile to export. Once the managerial class dominated them, the British lost everything that mattered to them as a nation.”

Europe is currently going through a long period of stagnation, and bureaucratic regulations and controls over the economy and energy production are always cited as one of the main reasons for this.

3. Cost-Disease Socialism

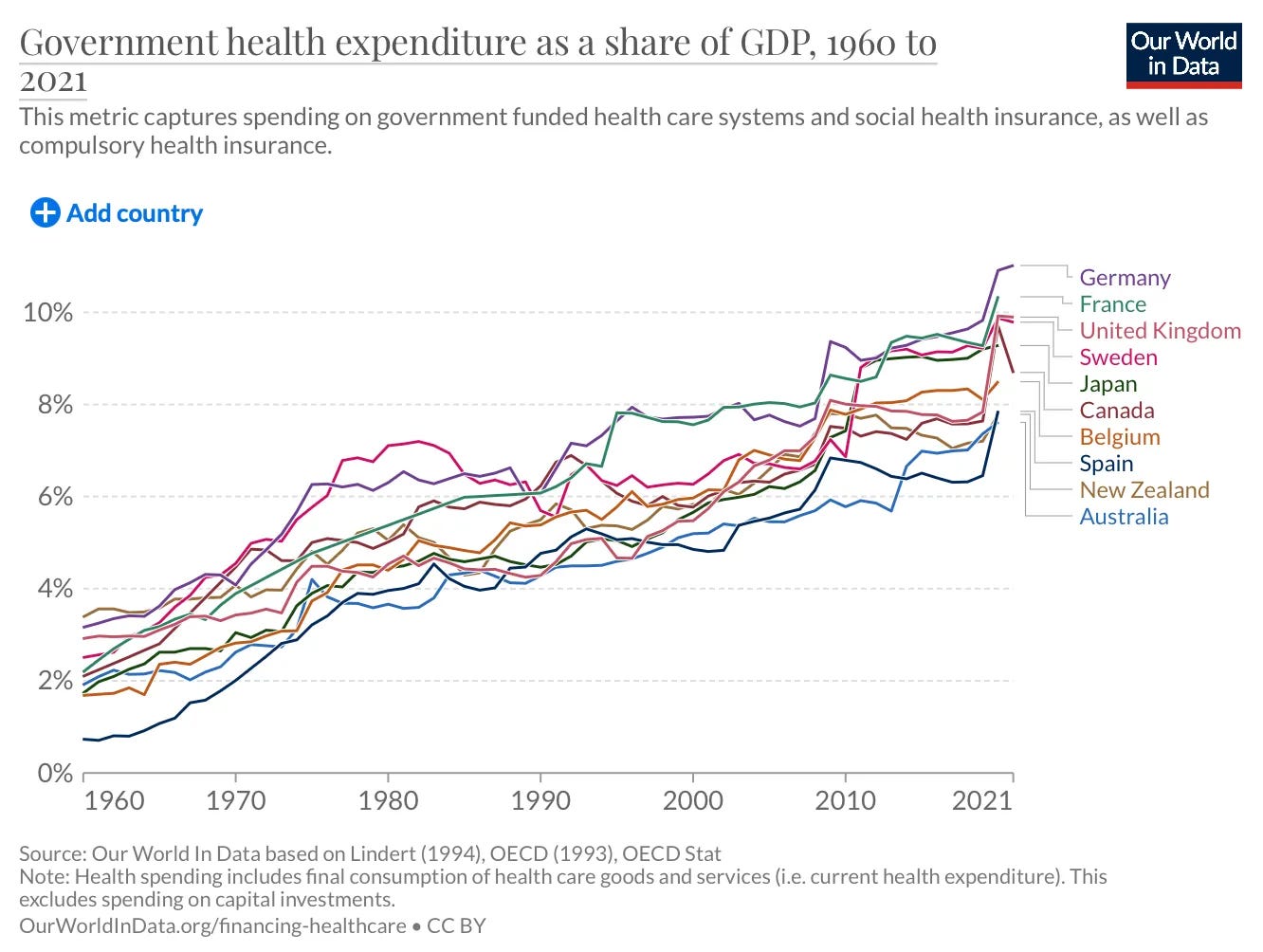

Have you ever wondered why the price of healthcare has only gone up for all governments that offer some degree of healthcare worldwide?

This can be explained by something called cost-disease socialism.

The healthcare sector has a large number of regulations, which causes administrative bloat. This increases the need to hire bureaucrats within the sector to comply with them, which adds costs.

In addition, the government subsidises the healthcare sector to keep prices down and make it affordable to more people. This increases demand for an inelastic supply, which increases costs in the long run.

Why would a subsidy increase costs when it is supposed to do the opposite?

The huge number of regulations and administrative bloat brings in diseconomies of scale, which is needed to meet the higher demand. Costing more to scale increases costs.

Secondly, the subsidies themselves, along with the high regulatory barriers to entry, reduce competition. Less competition means less incentive to reduce costs.

Ending

There is more to talk about the negative effects of bureaucracies, but let us leave it with three mechanistic examples of why bureaucracies are not good.